There’s nothing like the word Mahagathbandhan (Grand Alliance) to make even the most boosterish Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) supporter sweat a little. And it’s not just because of what happened in Bihar in 2015, when an alliance of the Rashtriya Janata Dal, Janata Dal (United) and Indian National Congress (INC) inflicted a defeat on the BJP. Ever since 1977, dominant parties – the INC until the 1980s, the BJP now – have been vulnerable to a united opposition challenge. Which is why Nitish Kumar and Lalu Prasad Yadav have both urged the INC to engineer a national-level grand alliance to break the BJP’s current ascendance.

Uttar Pradesh (UP) is of course the lynchpin of the BJP’s national dominance, having contributed 71 of its 282 Lok Sabha seats in 2014. That is why its recent state election victory was such good news for the party, since it places the BJP on a strong footing for the 2019 election, only two years away now.

The best way to stop the BJP juggernaut, at this point, seems to be a Mahagathbandhan in UP. After the Emergency, an opposition alliance forced the INC’s Lok Sabha seats in UP down from 73 (of 85) in 1971 to exactly zero in 1977. Its state assembly tally fell from 215 in 1974 to 47 in 1977. Little more than a decade later, another grand alliance knocked the INC down from 83 Lok Sabha seats in 1984 to 15 in 1989. In the state assembly, the INC dropped from 269 seats in 1985 to 94 in 1989. Grand alliances in UP have proved effective in countering dominant political parties.

Like the previous instances, a UP grand alliance might not be more than a stopgap. The Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) and Samajwadi Party (SP) have a history of animosity that won’t be easy to overcome, though the INC could play mediator between former rivals as it did in Bihar.

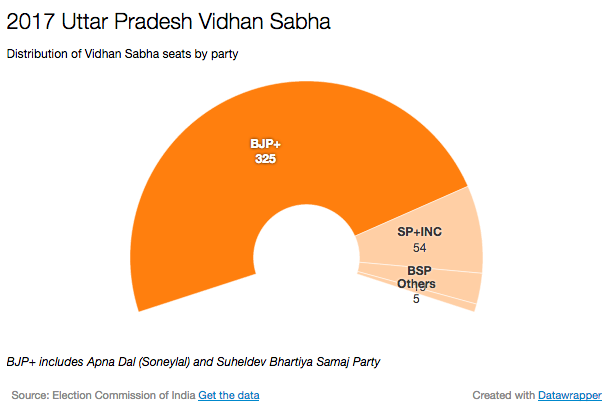

So what impact might a Mahagathbandhan have had on the just completed state elections? Here’s what the new UP state assembly looks like:

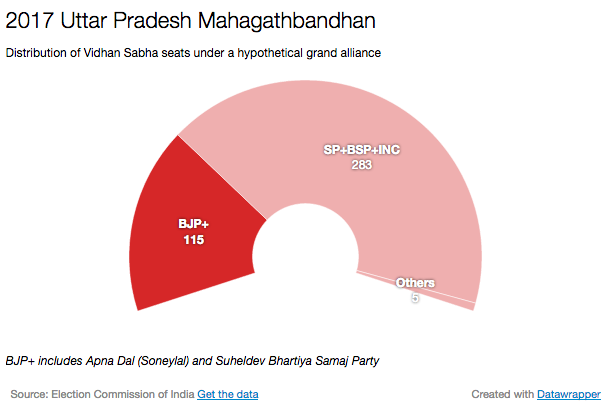

A simple addition exercise shows that the BJP and its allies exceeded the combined vote share of the SP, BSP and INC in 115 state assembly seats. If we include the Rashtriya Lok Dal (RLD), this number drops to 101.

What about the Lok Sabha? The BJP and its allies won more votes than a theoretical Mahagathbandhan in only 25 seats (24 if you include the RLD), compared with its 2014 tally of 73. The BJP would still have won the national election, but its Lok Sabha tally would have been down to (a still impressive) 236.

There are obvious caveats: it’s not clear that parties’s vote banks will seamlessly transfer to grand alliance partners. Some portion of BSP and SP voters who dislike the other party could instead vote for a third party, which could even be the BJP. Or party workers could be unenthusiastic for a candidate in their constituency from a different party. For instance, INC candidates on average won fewer votes in the 2017 UP election than did SP candidates, which political scientist Gilles Verniers sees as evidence that “SP supporters did not transfer their votes to Congress supporters to the same extent that Congress supporters did”.

On the other hand, a grand alliance that looks like a potential winner could gain votes purely on momentum. The Centre for the Study of Developing Societies’ 2014 National Election Study found strong evidence for such a bandwagon effect: 43% of voters said that they chose the party they thought was leading the race.

Either way, the compelling logic of a grand alliance in UP suggests that the parties the BJP defeated in 2017 will put in a serious effort to get one going. Whether it happens or not is the 80-seat question.